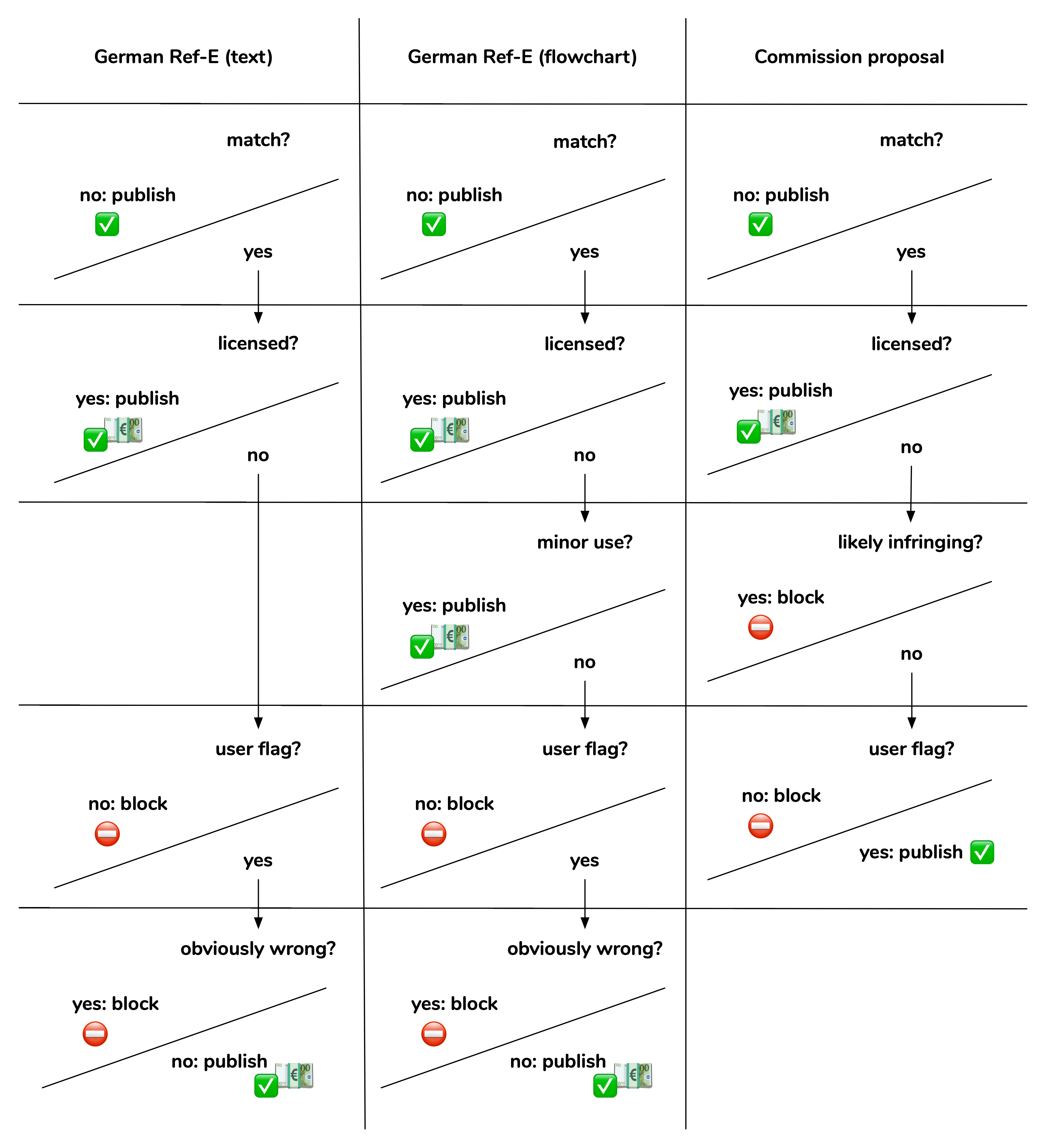

Comparison of mechanisms proposed for the practical application of Article 17(4) in compliance with Article 17(7)

-

This document compares the approaches presented by the Commission in the guidance consultation and by the German Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection (BMJV). For the BMJV we are comparing two different mechanisms. The mechanism contained in the text of the Referentenentwurf (“Ref-E”) and the mechanism depicted in a flowchart published by BMJV on the 16th of October. Scope

-

The comparisons in this document focus on scenarios in which OCSSPs use automated content recognition technology to match works included in user uploads to reference data provided by rightholders (i.e real time upload filters). The fact that some platforms will likely implement these types of measures does not mean that all platforms have to implement such measures. The document assumes that real time upload filters are only one way how platforms can meet the requirements imposed on them by Article 17 of the DSM directive. It further assumes that in line with the principle of proportionality, platforms can also implement other types of measures to meet these requirements. Such other types of measures are out of scope for this analysis.

-

The comparisons in this document also assume that the following additional user rights safeguards are part of any national implementation of Article 17:

- Provisions that require platforms to notify users of any automated matches that take place after a work has been successfully uploaded on a platform. In such cases users must be given a reasonable time to flag the matched use as legitimate. During this period the upload must remain available on the platform.

- Provisions that allow uploaders to flag works as being openly licensed or in the public domain. Ideally the resulting information would be stored in a centralized public database that must be consulted by any platform utilizing automated content recognition technology to match user uploads to reference information provided by rightholders.

- These additional user rights safeguards are currently missing from both versions of the German proposal and while the Commission’s proposed guidance does address the first scenario it is lacking safeguards for the second. A s a result, and regardless of the discussion below neither of these proposals currently meet the requirements established by Art 17.

Comparison

- The following table compares the intervention logic of the three different proposals. They are based on our own analysis of these proposals.

-

The logic as contained in the text of the German Ref-E seems flawed as the exception for minor uses contained in §6 only plays an indirect role in the mechanism 1. It can be invoked by users as the rationale for flagging a use as legitimate, and its criteria can be used when automatically assessing if a user flag is “obviously wrong”. However, it cannot be used as a first test to assess automatically if the use is legitimate. This minor role of §6 in the mechanism stands in no relationship to the importance of the safeguard that is introduced in §6.

- As a result of the absence of an automated check for minor uses, this mechanism will require user notification for every match that is not licensed, making this the mechanism that will lead to most notifications to users. F or this reason alone this approach should be brought in line with the mechanism described in the flowchart published by the BMJV.

-

The mechanism described in the flowchart published by the BMJV and the mechanism proposed by the Commission are structurally very similar. Both feature an automated test followed by the possibility for users to mark (“flag”) as legitimate the uses of matched works in their uploads. The main difference is the intention of the first automated test.

- The “likely infringing” test in the Commission’s model seeks to filter out uses of works that have a high likelihood of being infringing so that these can be blocked without ex-ante human intervention.

- The “minor use” test in the German flowchart model seeks to identify uses that meet pre-established criteria for minor uses so these can be published (subject to remuneration) without ex-ante human intervention.

- Both tests have the effect of reducing the number of matches that result in a notification of the user by automatically filtering out a class of uses that can be automatically detected with (high) accuracy.

User rights

-

From a user rights perspective the German flowchart model has a number of advantages over the model proposed by the Commission:

- In the German flowchart model users always have the opportunity to claim legitimate use before an upload can be automatically blocked. (To correct intentional wrongful claims of legitimate use, the German model has an additional automated “obviously wrong” test as a final stage).

- The automated “minor use” test in the German flowchart model will significantly reduce the amount of notifications to users. More importantly, instead of requiring users to make on-the-spot legal judgements that they may be ill-equipped to make, it would automatically authorise publication according to transparent criteria.

-

Conversely the Commission’s model has a number of corresponding drawbacks:

- If a use is considered to be “likely infringing”, the upload will be blocked without any human intervention.

- All matching uploads will be blocked unless the uploader makes a legitimate use claim (that requires the uploader to make on-the-spot legal judgments that they may be ill-equipped to make). Other stakeholders

-

From the platform perspective the German flowchart model has at least one major advantage over the Commission’s model. By automatically identifying “minor uses”, the amount of matches that result in user-notification will be significantly reduced. As a result there will be less user flags that trigger a resource intensive human review process that needs to be conducted by the platform. Conversely, the fact that “minor uses” are subject to remuneration will likely be perceived as a drawback by platforms.

-

From the creators and rightholders perspective, the picture is more complex. Some classes of rightholders are likely to reject either of these models outright because they disagree with the premises that they are based on. Still there are at least two clear advantages of the German flowchart model over the Commission’s model when seen from the creators perspective:

- As discussed above, the German flowchart model will result in fewer matches that require a user notification with the subsequent chance of a user flag that requires a human review by the platform. Such a human review requires rightholders to justify their blocking requests which means that it is resource intensive for them as well.

- Almost all uses in the German flowchart model are subject to remuneration either in the form of licensing revenues or direct remuneration rights. By focusing on enabling remunerated uses wherever possible the German flowchart model will likely lead to better economic outcomes for certain types of rightholders (primarily members of CMOs). Reconciling both models

-

The central element that sets the German flowchart model apart from the Commission model is the existence of the minor uses exception in §6 of the Ref-E. The criteria contained in this exception enable the automated check of minor uses and the exception provides the basis for the remuneration of minor uses.

-

While the Commission, in its consultation paper, acknowledges that Member States have room for such forms of authorisation when implementing Article 17 into their national laws, it seems unlikely that based on the limited mandate contained in Article 17(10) the Commission will actively recommend such an exception in its guidance.

-

However, the Commission could further fine-tune its model to bring it more in line with the German flowchart model, by modifying the (so far underdeveloped) “likely infringing” test with a provision that establishes minimal quantitative threshold for what can be considered to be likely infringing (such as the quantitative thresholds established in §6 of the German Ref-E).

- Uploads that contain matches that do not meet this threshold should be published, while at the same time notifying rightholders and giving them the ability to request removal (alternatively, Member States could put in place an authorisation mechanism for these uses like the one foreseen in §§6 and 7 of the German Ref-E).

- Uploads that contain matches that meet the threshold should result in a notification of the uploader providing her with the opportunity to flag the upload as legitimate. (In this scenario a final “obviously infringing” test in line with §12 of the German Ref-E would be justified as well).

-

Despite its name (“Mechanically verifiable uses authorized by law’’) there is nothing in the text of the proposal that actually prescribes its mechanical application by platforms. Instead it is repeatedly referenced in the context of pre-flagging as a justification for legitimate uses. This could be due to the condition that uses under §6 need to be non-commercial, which is difficult to automatically assess on a case by case basis. However, if the uploader is monetizing the upload, that fact could be taken as a proxy for commercial use. Another way of addressing this issue could be to allow users to flag their accounts as non-commercial. ↩︎