Explainer: What will the new EU copyright rules change for Europe's Cultural Heritage Institutions

On 17 May 2019 the Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (2019/790 - here-after DSM directive’) was published in the Official Journal of the European Union. As with all of the EU directives, the provisions contained in the directive will not apply directly, but will need to be implemented by each EU Member State in its national laws. The Member States now have until the 7 June 2021 for the implementation of the new rules into national law. Only after a Member State has completed the implementation process will cultural heritage institutions in that Member State be able take advantage of these new rules.

While it will still take some time before the new rules will have an effect, this is a good moment to take a closer look at the changes introduced by the DSM directive as it affects cultural heritage institutions. This is not only important in order to be prepared to make use of the new rules once they are in effect but also to help Member States’ governments understand the needs of cultural heritage institutions so that they can take this into account when implementing the directive.

In this report we will take a look at the provisions of the DSM directive that are most relevant for cultural heritage institutions. We will start by analysing the new rules dealing with access to Out of Commerce works (Articles 8-11) and the optional provision providing a legal basis for Extended Collective licensing (Article 12). We will then take a look at Article 14 that deals with reproductions of Public Domain works. Finally we will discuss the new exceptions for making preservation copies (Article 6) and for Text and Data Mining (Articles 3 and 4).

Enabling Access To Out Of Commerce Works (Articles 8 - 11)

From the perspective of cultural heritage institutions the provisions aimed at enabling institutions to make available Out of Commerce Works (OOCWs) contained in their collection are the most important change introduced by the DSM directive. Contained in Articles 8 - 11 of the directive (with corresponding recitals 29 - 43) these provisions are also one of the most complex parts of the new directive.

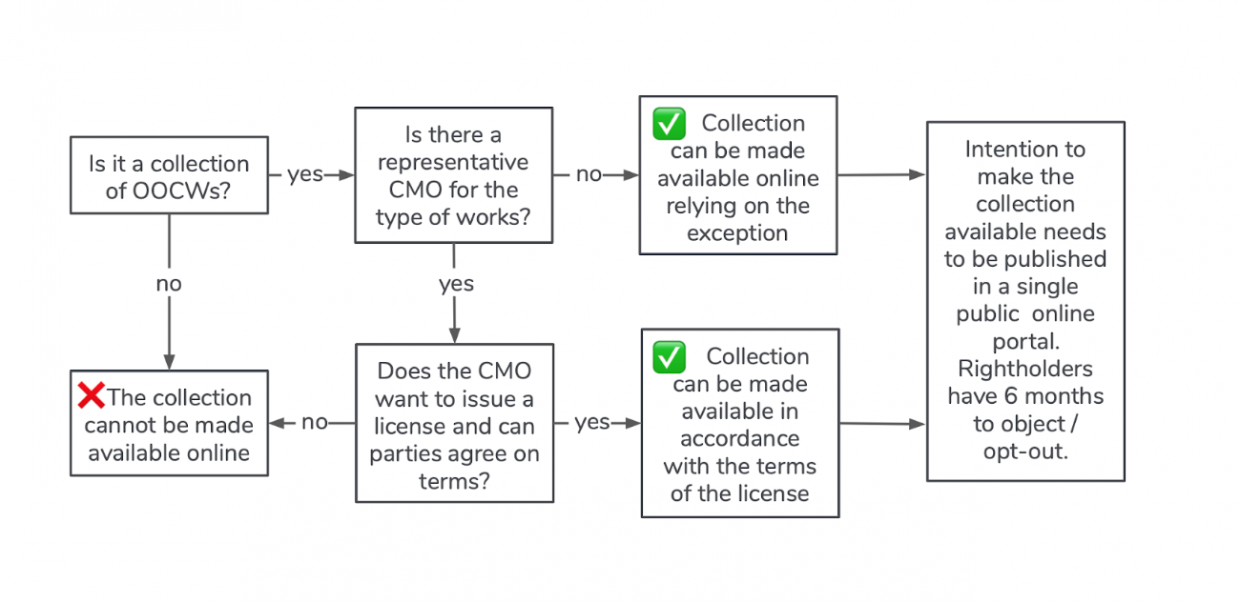

The objective of the new rules is to enable cultural heritage institutions to make Out of Commerce Works that they have in their collections available online without having to clear the rights on a work by work basis. The directive attempts to achieve this objective by introducing two mechanisms:

- As the primary mechanism it introduces the ability for representative collective management organisations to issue licenses for the use of OOCWs by cultural heritage institutions “irrespective of whether all rights holders covered by such a licences have mandated the collective management organisation” (in Article 8(1)).

- In situations where there are no representative collective management organisations that could issue licences for certain type of works cultural heritage institutions can rely on the secondary mechanism: a copyright exception that allows them to make Out of Commerce Works in their collection available online (Article 8(2)). In both cases rights holders must have the ability to opt-out (prevent the cultural heritage institutions from making their works available). In order to give them the ability to do so cultural heritage institutions and collective management organisations (CMOs) must publish information about the Out of Commerce Works in a “public single online portal” to be run by the EUIPO six months before they make the works available online.

This six month period is intended to give rights holders a real possibility to opt-out before their works are made available online (Article 10(1)). After the six month period has passed, the works can be made available on the website of the cultural heritage institutions for non-commercial purposes either under the terms of the licence granted agreed between the institution and a CMO or relying upon the exception. In either case, the cultural heritage institution does not carry the risk to be held liable for copyright infringement.

An overview of the process for making Out of Commerce Works available under the new provisions.

There are two obvious weak links in this process. First it may turn out too complicated for cultural heritage institutions to the identify substantial amounts of works as being Out of Commerce. According to the directive Works are Out of Commerces Works “when it can be presumed in good faith that the whole work […] is not available to the public through customary channels of commerce, after a reasonable effort has been made to determine [this] (Article 8(5)). While this definition makes a lot of sense for published works such as books and journals it will be much harder to operationalise for other types of works such as artworks, audiovisual works or photos (although recital 30 further clarifies that works were “never intended for commercial use or that they have never been exploited commercially” are included in the definition).

The second weak point is the fact that while the directive requires Member States to ensure that representative CMOs can issue licenses for collections of Out of Commerce Works that include works by non-members, it does not require them to do so. This means that CMOs can simply refuse to issue licenses for example because they are not commercially interesting for them. In situations where a representative CMO exists but does not (want to) issue a license the cultural heritage institution cannot proceed with making the the works available as the fallback exception only applies in situations where a representative CMO does not exist.

Dialogue with rights holders will be essential

Fortunately both of these weak points can still be addressed in a meaningful way during the national implementations of the directive. Article 11 requires Member States to “consult rightholders, collective management organisations and cultural heritage institutions in each sector” before establishing specific requirements for the determination of Out of Commerce status of works. Member States shall further “encourage regular dialogue between representative users’ and rightholders’ organisations, including collective management organisations, and any other relevant stakeholder organisations, on a sector-specific basis”.

This means that the question of how useful the directive will be in practice will depend a lot on a good collaboration between cultural heritage institutions and collective management organisation on the Member State level. At this national level these dialogues provide an opportunity for all stakeholders to agree on workable rules for determining the Out of Commerce status of collections, to make clear determinations for which types of works the fallback exception does not apply and to establish trust between cultural heritage institutions and CMOs that can facilitate the conclusion of licensing agreements once the directive has been implemented.

The crucial role of the public single online portal

In addition to good collaboration on the national level it will also be essential that the “public single online portal” that will be developed by the EUIPO be designed in such a way that it facilitates the process of making Out of Commerce Works available online. By designing the portal as a service aimed at facilitating the mass digitisation of OOCWs the portal could significantly boost the impact of the directive.

This means that in addition to the minimal requirements identified in the directive the portal should also serve as an information hub for CHIs wanting to digitise collections of OOCWs and as a persistent resource for information about OOCWs and opt-outs registered by right-holders. It needs to allow batch uploads via a web interface and APIs and support commonly used metadata formats used within the cultural heritage sector. To be meaningful for visual works the portal further needs to allow the publication of reduced size thumbnails as part of the required identifying information.

All of this requires that the EUIPO closely involves all relevant stakeholders (cultural heritage institutions, collective management organisations and other rightholders) in the design process.

A unique opportunity

Despite their apparent complexity the new rules for Out of Commerce works have the potential to break open the gridlock that many cultural heritage institutions face when digitising their collections. Embedded in the implementation process is an opportunity for cultural heritage institutions to make their voice heard within their Member States. This means working with the relevant government officials to allow them to understand the needs and realities of the cultural heritage sector. Equally important this also means engaging in a dialogue with CMOs and rights holders to identify practical arrangements that work for both sides.

Collective Licensing With An Extended Effect (Article 12)

Article 12 of the directive allows (but not requires) Member States to introduce extended collective licensing (ECL) schemes that go beyond the relatively narrow case of Out of Commerce works discussed in the previous chapter. It provides a legal basis for extended collective licensing (i.e licenses issued by collective management organisation that also apply to works by rights holders not represented by them) in “well-defined areas of use, where obtaining authorisations from rights holders on an individual basis is typically onerous and impractical”. While not limited to cultural heritage institutions as beneficiaries (ECL is widely used to enable educational uses of copyrighted materials in some EU Member States) this provision may also be of interest for cultural heritage institutions as could enable the digitisation of entire collections regardless of their copyright status (i.e. Out of Commerce and in commerce works together) under a single licensing agreement.

Compared to the provisions on the use of Out of Commerce works, an important drawback of licenses enabled by this provision is that they only apply domestically. This means that the licensed works can only be made available to users in the Member States where the license has been concluded. This means that cultural heritage institutions would need to geo-block access to collections that they make available online by relaying on a ECL license. As long as this is the case (the article includes a clause that asks the European Commission to review the restriction on cross border use within the next 2 years), Article 12 will remain problematic from the perspective of cultural heritage institutions interested in the the widest possible access to their digitised collections.

Works Of Visual Art In The Public Domain (Article 14)

Article 14 of the directive clarifies a fundamental principle of EU copyright law. The article makes it clear that “when the term of protection of a work of visual art has expired, any material resulting from an act of reproduction of that work is not subject to copyright or related rights, unless the material resulting from that act of reproduction is original”. In other words, the directive establishes that museums and other cultural heritage institutions can no longer claim copyright over (digital) reproductions of public domain works in their collections. In doing so the article settles an issue that has sparked quite some controversy in the cultural heritage sector in the past few year and aligns the EU copyright rules with the principles expressed in Europeana’s Public Domain Charter.

In practice this means that those in which non-original reproductions enjoy protection via neighbouring rights (such as it is the case in Spain or in Germany) will now have to modify their laws so that such rights can no longer be claimed in the case of reproductions of visual art works that are in the public domain. It is important to note here that the wording of the new article 14 does not only cover photographic reproductions of two-dimensional artworks (such as paintings) but also covers 3 dimensional reproductions of 3 dimensional works (such as 3D scans of sculptural works).

While this provision will require cultural heritage institutions who have so far claimed rights over the reproductions of public domain works to make some adjustments to their practices (i.e they can’t rely on copyright to impose restrictions on the re-use of digital reproductions that they make available to the public) it is also important to understand that this does not mean that they have to give them away for free. Institutions remain free to sell reproductions for example in the form of postcards or posters as noted in recital 53 of the directive.

A New Mandatory Exception For Preservation Copies (Article 6)

Article 6 of the directive contains another provision that is specifically targeted at cultural heritage institutions. It requires Member States to implement an exception in their national laws that allows cultural heritage institutions “to make copies of any works […] that are permanently in their collections, in any format or medium, for purposes of preservation of such works”. While a number of Member States already have similar exceptions in their copyright laws, this new exception ensures that cultural heritage institutions in all EU Member States can make preservation copies of the works that they have in their collections. Recital 28 further clarifies that Cultural Heritage Institutions can “rely on third parties acting on their behalf and under their responsibility, including those that are based in other Member States, for the making of copies”. This last addition is an important clarification as it provides room for the sharing of digitisation equipment via (cross border) digitisation networks, and allows the use of external contractors when creating preservation copies.

Text And Data Mining (Articles 3 & 4)

Finally the DSM directive introduces not one but two new Text and Data Mining exceptions (Articles 3 & 4) that will need to be implemented by all Member States. The first exception (Article 3) allows “research organisations and cultural heritage institutions” to make extractions and reproductions of copyright protected works to which they have lawful access “in order to carry out, for the purposes of scientific research, Text and Data Mining”. Under this exception cultural heritage institutions can text and data mine all works that the have in their collections (or to which they have lawful access via other means) as long as this happens for the purpose of scientific research.

The second exception (Article 4) is not limited to Text and Data Mining for the purpose of scientific research. Instead it allows anyone (including cultural heritage institutions) to make reproductions or extractions of works to which they have lawful access for Text and Data Mining regardless of the underlying purpose. Rightholders can exclude their works from the scope of the exception by expressly reserving their rights “in an appropriate manner, such as machine-readable means in the case of content made publicly available online”.

Taken together these two exceptions provide cultural heritage institutions with ample room for Text and Data Mining. In cases where rightholders have reserved their rights and they cannot rely on the general exception introduced in Article 4, they can fall back on the scientific research specific exception in Article 3. It is important to understand that the scientific research specific exception does not only apply in situation where the cultural heritage institution is carrying out the research but also in situations where it enables external researchers to Text and Data Mine works in its collections.

The directive leaves some room for stakeholders to define some of the modalities of Text and Data Mining such as the standards for storing copies made in the process (Article 3(2)) and the measures that rightholders may implement “to ensure the security and integrity of the[ir] networks and databases” (Article 3(3)). It will be important that cultural heritage institutions contribute to these discussions while coordinating their input with the organisations representing the interests of researchers and research organisations.

Next steps

Taken together the provisions discussed above have the potential to significantly improve the position of cultural heritage institutions in Europe.

While most of these provisions leave relatively little room during the implementation there is a significant opportunity for cultural heritage institutions to engage with national policy makers and make their preferences and potential concerns heard. This will be especially important for the parts of the directive dealing with Text and Data Mining and with access to Out of Commerce works. Here national lawmakers have considerable room for maneuver when implementing the directive.

While Member States have until the 7th of June 2021 to implement the rules, the time to engage with national lawmakers (and to reach out to other stakeholders) is now as most decisions tend to be made early in the implementation process.